Day four of riding through the Huadong Valley of eastern Taiwan in 2018 began in Yuli, the midpoint of this bicycle trip from Hualien City to Taitung City. From the weather report I knew I’d have another challenging ride ahead—yet again the mercury was due to exceed 35 degrees. Luckily I was in no great rush, as I had allocated an entire week for a trip that experienced riders could easily manage in two days. I made good use of that extra time, making numerous stops and detours to document some of the many historic and cultural sites along the way, many of them quite obscure. I ended the day in Guanshan, slightly more than 40 kilometers down the valley.

My first order of business after a healthy breakfast1 was to conduct a survey of Yuli’s historic cinemas. The earliest theater in Yuli was likely a multi-purpose performance venue built primarily with wood2. Located on the central roundabout, it was eventually replaced with a reinforced concrete structure with seating for 700 patrons, probably in the early 1940s. After the arrival of the Kuomintang (KMT) it was among 19 theaters designated for nationalization—but there appears to be some disagreement about whether it was actually seized along with the others in 1947. It is generally remembered as Tiānshēng Theater (天聲戲院) but was listed as Xīnguāng Theater (新光戲院) in KMT party records3. It was demolished long ago.

A little further east one will find the former site of Yùshān Theater (玉山戲院), likely founded in the 1950s. With a capacity of 8654, it was slightly larger than the competition. After it closed sometime in the 1980s or 1990s it was supposedly turned into an arcade. As with the former Ruisui Theater, featured in the previous update, it has now been replaced by an outpost of the Tǒngguān Supermarket (統冠聯合超市, generally written as Tkmart), a chain popular across eastern Taiwan. Whether any part of the original structure remains is unclear.

I was eager to explore the remains of Yùdū Theater (玉都戲院) after finding it in a search of the relevant business records5 prior to embarking on this road trip, so I was quite disappointed to arrive and find it already undergoing renovations. Founded in 1968 near the front of the train station, it was the largest and most luxurious theater in town when it was built. Only a small part of its distinctive yellow facade could still be seen. From what I know it is now an outpost of the increasingly ubiquitous Poya (寶雅) chain of cosmetic stores.

An old man noticed my interest in Yudu Theater and provided some useful tips about the locations of another theater in town. It was on my list but I hadn’t been able to uncover any details nor locate it on satellite maps—and as soon as I learned where it was, it all made sense. Movie theaters are typically situated near the busiest parts of the commercial centers of small towns like Yuli but Xīnxīng Theater (新興戲院 or 新星戲院) was built in a residential area on the north side of town, far from the action. As with the others it closed sometime in the 1990s, after which it was converted into an auto mechanic shop. It is now abandoned and I did not find any obvious means of entry.

A brief introduction to Yuli, for context: as the largest settlement in the central Huadong Valley it has long been a regional transportation hub. Prior to the arrival of Chinese settlers in the late 19th century the area was inhabited by several Taiwanese Indigenous groups: the Amis people, who called it Posko6; the mountain-dwelling Bunun; and a variety of Plains Indigenous people who emigrated from western Taiwan beginning in the 19th century (a story elucidated later in this post). The opening of the 152 kilometer-long Bātōngguān Trail (八通關古道) in 18757 greatly increased the inflow of Han Chinese settlers, and this trend continued after the arrival of the Japanese, who renamed it Tamazato (literally “Jade Village”, which is where the name Yuli comes from in Mandarin Chinese) in 1920.

Yuli thrived as an administrative center and important market town throughout the Japanese colonial era but few relics remain from those days8. Apart from the newly-restored Yuli Shinto Shrine (玉里神社), the subject of a full post on this blog, another example worth mentioning is the reinforced concrete Yuli Credit Union (玉里信用組合). Completed in 1930, it is located behind the more modern office of the local farmers’ association on the north side of town. It was designated a heritage property in 2006 but it doesn’t seem as if any effort has been made to restore it.

Eastern Taiwan underwent a population explosion in the 1960s, a consequence of the opening of the Central Cross-Island Highway (中部橫貫公路) and the introduction of numerous government-sponsored development projects employing huge numbers of KMT veterans9. Boom turned to bust in the late 1980s as rising wages and policy changes restricting mining and forestry reduced employment opportunities in the valley. At its peak Yuli was probably home to around 50,000 residents, but nowadays fewer than 25,000 remain. Yuli is not alone in experiencing population outflow—the entire valley is hollowing out as people relocate to the bigger cities on the other side of the Central Mountain Range.

I headed south out of town to link up with the scenic Yuli-Fuli Bike Trail (玉富自行車道). This bikeway follows the former railway line, which jogged eastward across the continental divide. That line was planned in the 1920s, decades prior to the acceptance of plate tectonics theory, so we can excuse the builders for not realizing how much trouble they’d be causing future generations. The convergence rate between the Philippine Sea Plate (to the east) and the Yangtze Plate (part of the larger Eurasian Plate to the west) is 2 or 3 centimeters per year, high enough that the railway authority ended up having to invest considerable time and energy in maintaining the bridges that cross the divide. As such, the entire line was rerouted to the western side of the valley beginning in 1989—and after many years of neglect the former line was converted into the bikeway seen here.

On the eastern side of the valley I made a small detour into Hālāwān (哈拉灣; Harawan or Harwan in the local tongue), a village nestled into the foothills of the coastal mountains. Halawan is home to a mixed settlement of Amis and the descendants of Plains Indigenous people from southwestern Taiwan. It was also home to a modest Shinto shrine during the Japanese colonial era, but not much remains of this apart from a couple of stone lanterns and a torii renovated in a vaguely indigenous style10.

Back on the bikeway I breezed by Āntōng Station (安通車站), originally established in 1924. Antong has long been famous for its hot springs—there’s even an original Japanese onsen in the hills beyond the station. This was also the western terminus of the Antong Traversing Trail (安通越嶺古道), a continuation of the Qing dynasty Batongguan Trail connecting the Huadong Valley with the Pacific coast. Although rehabilitated as a bicycle service center after the bikeway opened, as of 2018 this station is once again abandoned. There’s really no need for a full-fledged rest station on this route anyhow—it isn’t a long bikeway, nor is any climbing required.

Soon I crossed into Fuli, the southernmost district of Hualien, and came to the end of the line, Dongli Railway Station (東里鐵馬驛站). Unlike the derelict station in Antong this one was open to the public and staffed with several friendly locals. The interior had the feeling of a community center as much as a rest stop—and noticing that they served coffee, I ordered one on ice and sat beneath a fan for awhile, planning my next move. Idle curiosity led me to the station front—and here I noticed several placards with information about local attractions, none of which I had noted in advance research. Intrigued, I soon set forth for a quick ride around the neighbouring settlement of Dàzhuāng (大庄, literally “Big Village”).

Dazhuang might not look like much to an unprepared outsider but it has quite a fascinating history. Situated in a contact zone between the traditional territories of Amis and Bunun peoples, it was settled by several waves of Plains Indigenous peoples (平埔族群) escaping the encroachment of Han Chinese settlers on their lands in southwestern Taiwan. Beginning in the late 1820s many groups of Taivoan (大武壠族), Makatao (馬卡道族), and Siraya (西拉雅族) people made the long overland journey to this far frontier, which was not directly administered by the Qing until the establishment of Taitung Prefecture in 188711. After the Japanese conquest of Taiwan many Hakka migrated here from other parts of the island, initially on their own, and later with the encouragement of the colonial government12. Nowadays the settlement remains mixed, with the largest population of Plains Indigenous people in eastern Taiwan living alongside Hakka and Han Taiwanese.

Dazhuang Public Shrine (大庄公廨) is the only Plains Indigenous shrine in eastern Taiwan. These shrines are generally known as kuba, although many variations exist in different languages and dialects spoken by the Plains Indigenous peoples13, as with all other terms in this section. Kuba serve as halls of worship as well as community meeting spaces, and they are the sites of important ceremonies and rituals. This particular shrine venerates an ancestral spirit known in Mandarin Chinese as Ālìzǔ (阿立祖), embodied by the liquid contained within ritual vessels resting on the ground inside the shrine. The interior features a central column with a bamboo fishing trap where the spirits rest14. As with other Plains Indigenous shrines in Taiwan, this one also displays the influence of Han Taiwanese religious customs; note the divination blocks (筊杯) resting on the low stone altar and the incense burner in front of it. The intermixing of Taiwanese folk religious and Plains Indigenous customs is a consequence of the long decades of colonial suppression (both Japanese and KMT), during which Indigenous spiritual practices went underground, often by integrating with accepted customs.

Chiu’s Historic House (邱家古厝) is a rare example of an antique Hakka mansion in eastern Taiwan. It was constructed in the early 1930s with timber imported from Fujian Province and features two delicately-carved sandstone pillars out front. The Qiu family emigrated from the Liutui (六堆) area of southwestern Taiwan15 around the turn of the century and became prosperous and influential after Qiū Āndé (邱安德) opened Yǎngyuán Pharmacy (養元中藥房). He was among the most important Chinese doctors in eastern Taiwan during the Japanese colonial era and became the village chief for some time. Although it isn’t explicitly stated in any text I’ve consulted, the pharmacy was probably the exclusive liquor and tobacco dealer in the area, which would have certainly helped fund the construction of such an ornate house. Unfortunately the structure was severely damaged in the 1951 East Rift Valley earthquakes and Typhoon Bilis (碧利斯颱風) in 2000. Despise these hardships the house was designated a heritage property in 2002 and some effort has been invested in making it an interesting place to visit16.

Soon I was heading south again, barrelling down Provincial Highway 9 in the late afternoon heat. Between settlements the verdant landscape unfolded, with vast expanses of rice paddies stretching to the foothills of the Central Mountain Range. I made another brief stop for coffee at Remote Mountains Cafe (富里深山咖啡館) before noticing the ruins of an old tobacco barn next to Dōngzhú Elementary School (東竹國小)17. Nothing more eventful transpired before arriving in central Fuli, around 12 kilometers down the line from Dongli.

I was excited to finally visit Ruìwǔdān Theater (瑞舞丹大戲院), perhaps the best-preserved vintage cinema in all of eastern Taiwan, but I wasn’t able to gain access. It opened in the early 1960s, one of four theaters in Fuli18, and closed in 1998 after a Lunar New Year screening. Recently it has enjoyed a second life, and it opens for special events and screenings around once every month. I was hoping I might find the owner and ask for a quick look inside—but nobody knew where he was when I came calling. I hope to return some day to properly document this historic wooden theater so I won’t say much more about it here.

I left central Fuli behind and formally entered Taitung County as the sun was slipping beneath the horizon. With dusky skies overhead I cruised into Chishang, another township famous for its high-grade rice harvest—as well as Taiwanese bento boxes. I was intent on visiting a famous theater in town while I still had enough light for photography so I buzzed by the main strip and crossed the railway line. Here I successfully located and explored Wǔzhōu Theater 五洲戲院, the subject of a full post on this blog.

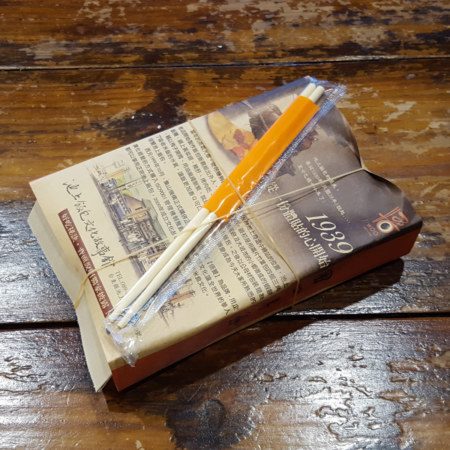

Having achieved my primary objective in town I crossed back to the east side of Chishang and indulged in a late lunch at the Wùtāo Bento Box Museum (悟饕池上飯包文化故事館). Just as Yonghe is famous for soy milk, Chishang is the place most strongly associated with bento boxes (biàndang 便當) in the Taiwanese imagination19, so that’s exactly what I ordered. Wutao is a chain, and I was most definitely dining in a tourist trap, so I wasn’t overly surprised that this particular bento box was lacklustre, but it was still quite satisfying after a long day on the road. I wandered around the “museum”, such as it was, and made sure to capture the vintage movie theater posters20 on display before making an exit.

By now it was too murky for good photography so I put my camera away, bypassed the scenic rice paddies south of central Chishang, and focused on the ride to Guanshan. Without being able to see much on the increasingly dark country roads I have little to report from this segment of the journey. Eventually I arrived in town to find lodging for the night and attend to necessities like a shower and a proper dinner. With options limited as evening wore on I opted to sample the eponymous Guanshan Bento Box (關山便當), mostly to see how it compared to the one I had earlier. This bento was far more satisfying, and I went to sleep feeling very positive about the day’s ride.

In the next entry I will document the remainder of the trip to Taitung City.

- I’m fond of sampling famous local breakfast fare when I’m on these road trips. On this particular day I swung by the Xīnxīng Street Sesame Flatbread Shop (新興街燒餅店) and had a breakfast sandwich with eggs, vegetables, and sprouts (a rather unusual ingredient by Taiwanese standards). ↩

- The earliest name for this theater was Chitose (千歲座 or 千歲館 in Japanese). It seems plausible that its name was changed after it was rebuilt—although that might also have taken place after the arrival of the KMT in 1945. ↩

- Dealing with the KMT’s ill-gotten movie theaters was an election issue leading up to 2004. More information about the KMT seizure of movie theaters can be found here ↩

- Except where otherwise mentioned, theater capacities on this blog are sourced from the Taiwan General Guide (台灣通覽), published by Ta-Hwa Evening News (大華晚報社) in 1960. ↩

- Business records have been a useful means of locating old theaters around Taiwan. Here is the entry for Yudu Theater. ↩

- Posko was transliterated into Hokkien as Phok-sik-koh (Púshígé 璞石閣), which alludes to the marble outcrops along the Xiùgūluán River (秀姑巒溪) that have the appearance of unpolished jade. ↩

- The construction of the Batongguan Trail was an enormous undertaking directed by Qing military commander Wu Kuang-liang (吳光亮), who was tasked with implementing the “open the mountains and pacify the savages” (開山撫番) policy. The Japanese later expanded and rerouted the trail, which became the Batongguan Traversing Trail (八通關越嶺古道). ↩

- One important Japanese colonial site I neglected to photograph on this trip is the Yuli Police Station (玉里警察官吏派出所, originally 璞石閣警察官吏派出所), which traces its history back to 1899. I doubt much of the current structure is quite that old—it has been renovated several times over the years—but it was certainly among the first police stations established in the Huadong Valley. ↩

- This demographic shift is described over and over again in my writing about the Huadong Valley so I won’t repeat the entire story here; just read some of my other posts in this series and you’ll find out much more about it. ↩

- For reference, the former Shinto shrine in Halawan is known by many names: 哈拉灣神社, 樂合神社, 下撈灣祠, and 洛和社. Read more about it (in Chinese, of course) here, here, and here. ↩

- The imposition of foreign rule led to open rebellion in 1888, a historic event known as the Dazhuang Incident (大庄事件), in which an alliance of Plains Indigenous, Amis, Puyuma, and Hakka fought battles all up and down the Huadong Valley, only to be defeated after Qing reinforcements arrived. For more information about the current status of the Plains Indigenous peoples mentioned here try these English language articles about the Taivoan, Makatao, and Siraya. ↩

- The Hakka migration from 1906 to around 1930 is sometimes referred to as the “second migration” (二次移民). The Japanese colonial authorities were intent on developing eastern Taiwan for agriculture and went to some lengths to attract Hakka farmers (e.g. by providing five years of free rent), who they felt would be more industrious and productive than in the Indigenous people already living there. A census taken in 1932 by the Japanese colonial authorities recorded a mixed population of approximately 1,600 residents in Dazhuang: 780 Taiwanese Indigenous people, 500 Hakka, and 240 Fujianese, among others. This population data is featured on the Chinese language Wikipedia entry for Dazhuang and derives from a book by the title of 大庄平埔西拉雅族文物圖說與民俗植物圖誌 by 張振岳. I’m guessing this information ultimately derives from the 1930 Taiwan Census. Note: Japanese statistics typically identify Hakka as Cantonese people, for many Hakka settlers in Taiwan trace their ancestry to northeastern Guangdong. ↩

- “Public Shrine” is the English translation on the placards by the front of Dongli Station. The Chinese characters (公廨; gōngxiè in Mandarin Chinese) are borrowed from a Japanese transliteration (kōkai) of what is likely a Makatao word (konkai). Taivoan people typically call these shrines kuba (or some variation thereof; kuma, kuva, and kuwa also appear in the literature). Whichever way it is spoken, it doesn’t exactly translate to “public shrine”; the meaning is perhaps closer to “clubhouse”, which is reflected in another common Chinese word for these cultural institutions, huìsuǒ (會所). ↩

- This bamboo fishing trap is known as the kogitanta agisen in the Taivoan language (Xiàng Shénzuò 向神座 in Mandarin Chinese, literally “seat of the Xiang Dieties”) according to the Wikipedia entry for Taivoan people. Additional information about the rites and customs of the Plains Indigeneous people of Dazhuang can be found in Chinese here and here. ↩

- For more about the history of the Liutui Hakka check out this post about a bicycle trip through the area. ↩

- More information about this old house can be found in the Chinese language blogosphere; for this post I consulted sources here, here, and here. ↩

- This same tobacco barn is featured at the bottom of this post cataloging some of the tobacco barns of Ruisui. I write more about the history of tobacco cultivation in the Huadong Valley in a previous entry in this series. ↩

- No trace remains of the other theaters in town. Fuli Theater (富里戲院), with a capacity of 650, was located somewhere Zhongshan Road. I’ve also learned of the existence of Dongli Theater (東里戲院), with a capacity of 500, but have no idea where it might be located. More information about the history of cinema in Fuli Township can be read (in Chinese) here. ↩

- Read more about Taiwanese bento box culture here and here. ↩

- Chishang reputedly had three movie theaters in its heyday. Apart from the aforementioned Wuzhou Theater, which is still standing, Chishang was also home to Yùshān Theater (玉山戲院), rebuilt after a fire with a capacity of 1,000, and Guāngmíng Theater (光明戲院). I’ve not found any trace of either of these—apart from the posters in the lunchbox museum anyway. ↩

Great photos with an absorbing text. Your remark “…hope to return some day…” gets a gloomy undertone with the virus blocking a holiday trip to Taiwan.