Zhōnghuá Theater (中華大戲院) is an impressive KMT authoritarian era ruin in Guanshan, a small town of approximately 8,800 in the idyllic Huadong Valley of Taiwan. With seating for 1,200 patrons it was the largest theater in Taitung when it opened in 1965, and it soon earned the title “northern tyrant” (běibàtiān 北霸天) for dominating the cinema industry at this end of the county. What explains the existence of such a huge theater in this remote, sparsely populated place? As with the more modest and folksy Wǔzhōu Theater (五洲戲院) in neighbouring Chishang, a closer examination of regional socioeconomic history provides answers.

Guanshan was once home to as many as five movie theaters1, an impressive number for a district with only 8,800 residents today. But Guanshan wasn’t always such a backwater—as with most other small towns in Taitung it experienced a massive increase in population and economic activity after the completion of the Central Cross-Island Highway (中部橫貫公路) in 1960. The opening of this highway dramatically increased access to eastern Taiwan, which had previously been only tenuously connected to the rest of the country2, and facilitated a rapid expansion of industry and natural resource extraction3. Government and military development programs flush with American foreign aid provided employment opportunities and incentives for migrants (many of them retired KMT veterans) to relocate to the southeastern frontier, and the population almost doubled in less than a decade4. All of this occurred against the backdrop of the Taiwan Miracle, a period of explosive growth coinciding with the golden age of cinema in Taitung County.

The name of this theater alludes to Greater China (大中華) and, as you might expect, it was co-founded by a military veteran, a former major general in the ROC army, Xú Jìnshēng (徐進昇). Born in Guangdong in 1908, he fought in the Chinese Civil War and eventually attained the rank of major general. He came to Tainan in 1950 and eventually retired from the armed forces to enter private enterprise, but his businesses did not do so well, and by 1961 he was seeking other opportunities5. His younger brother, Xú Huànguāng (徐煥光), had already relocated to Chishang, and recommended opening a theater with the help of a local doctor of Chinese medicine, Chén Jīnshān (陳金山). Xu Jinsheng moved to Guanshan in 1963, oversaw construction of the theater starting in 1964, and spent the rest of his life, alongside his son Xú Jiàndōng (徐建東), managing daily operations after it opened in 1965.

Movie theaters operating during the many decades of martial law (a period generally known as the White Terror) were subject to oversight by the police, and it was mandatory to stand for the ROC national anthem before every screening. This theater, operated by a veteran and so obviously aligned with the aspirations of the ruling KMT, presumably would have been subject to fewer inspections and the like. Indeed, the owner was almost certainly enthusiastic in promoting patriotic films, offering discounts for veterans, and screening free films on national holidays6.

Another interesting KMT connection is revealed by taking a closer look at the characters on the facade. Four characters to the left of the name of the theater credit the calligrapher; they read “written by Bái Shìwéi” (白世維題). Naturally I was curious about the artist—so you can imagine my surprise when I learned he was a KMT police officer famous for assassinating the warlord Zhāng Jìngyáo (張敬堯) in 1933. After 1949 he retreated to Taiwan with the KMT, became chief of police in Kaohsiung and Tainan, and eventually entered local politics. Presumably Xu Jinsheng knew Bai Shiwei through their shared experiences in the ROC army and in Tainan, although this isn’t explicitly stated anywhere to my knowledge. Whatever the case, you’re not likely to find another cinema adorned with an assassin’s calligraphy7.

Another common feature of KMT iconography can be found resting against some of the seats in the main hall: a popular portrait of generalissimo Chiang Kai-Shek, supreme leader of the Republic of China until his death in 1975. This portrait was originally shot on black and white film by Wáng Guìxùn (王貴遜) of the Guānghuá Film Studio (光華照相館) in Chongqing, the provisional capital of the ROC, in 1943. It was colorized by the same film studio in 1946 to mark the occasion of the president’s 60th birthday, imbuing the photograph with an almost beatific glow, rosy cheeks and all. Apparently Chiang was quite enamored with this portrait, which is why it became a mainstay of the cult of personality promulgated throughout the Republic. It is also the portrait you will find on his Wikipedia entry! Here I have reversed the work of the film studio, presenting it in the original black and white, mostly out of a healthy appreciation for the absurd.

Taiwan’s economic growth continued into the 1980s despite the energy crisis of the previous decade but the local economy in Taitung did not fare as well. Both the agriculture and logging sectors underwent downsizing, and a population outflow began that continues unabated to this very day. At the same time, families who had saved through the booming years of the 1960s and 1970s could now afford televisions and home video, further thinning audiences. Zhonghua Theater was also used for puppet shows, traditional Taiwanese opera, graduation ceremonies, and local events, but in the early 1980s there were no longer throngs of people attending every film screening, and soon the numbers dwindled to unsustainable levels. In 1985 it closed forever8, and until recently, was only used for storage.

Zhonghua Theater was listed for sale in 2020 and was soon sold. Shortly after the Mid-Autumn Festival in 2021 the body of the theater was demolished, leaving only the front part of the building intact. Local residents commemorated the old cinema by organizing one final screening in the clearing where the theater once stood9.

For more information about this theater check out this excellent feature, which documents several derelict theaters in Taitung; this television news segment; and these photos.

- I’m uncertain about the total count as the rest have been demolished and it’s unclear how many of these were contemporaneous. From my notes, these include the eponymous Guanshan Theater (關山大戲院), formerly located somewhere near the main Mazu temple; Liánhé Theater (聯合戲院), also located next to the Mazu temple (which opens the possibility that these first two are the same theater); Dōngshān Theater (東山戲院), located near the old vegetable market somewhere around Zhonghua and Minsheng, known for showing the same film reels as Wuzhou Theater in Chishang; and finally the Japanese colonial era Lilong Theater (里壠劇場), originally located where the “35 Chicken Rice” shop is on Heping Road. Prior to 1937 Guanshan was known as Lilong, or Rirō in Japanese, a name derived from an Amis word for a species of red mite. ↩

- Prior to the opening of the Central Cross-Island Highway only the dangerous Suhua Highway and remote South-Link Highway, both built by the Japanese in the 1930s, provided road access to eastern Taiwan. The eastern railway network was only connected in 1979 with the completion of the North-Link Line, and it wasn’t until the South-Link Line opened in 1991 that an around-the-island tour by rail became possible. ↩

- Taitung Datong Cooperative Farm (台東大同合作農場), one of the main government projects in the region, was founded in 1954, and regularly expanded and reorganized through the 1960s as thousands of newly-retired veterans poured over the central mountains into eastern Taiwan. This article (in Chinese) has an interesting perspective on the disappearing legacy of agricultural development in Taitung. ↩

- Taitung County had a population of approximately 160,000 in 1956; by 1970 that number had swollen to nearly 300,000, but it has been falling ever since. As of 2015 the population was down to 222,452 with no sign of a recovery. Military veterans are commonly referred to as róngmín (榮民), or “honored citizens”. ↩

- Biographic details in this section were sourced from this entry in the Taiwan Cultural Memory Bank. ↩

- Some of these details were gleaned from this post about the old theater. ↩

- The fact that Bai would have taken up calligraphy as a hobby is no great surprise. Despite their ruthlessness, the KMT also celebrated many aspects of traditional Chinese culture, and it was fairly common for members of the establishment to dabble in poetry, painting, calligraphy, and so on. Similarly, Bai’s elevation to police chief and political office under martial law demonstrates another KMT tendency: rewarding party loyalists with plum positions. ↩

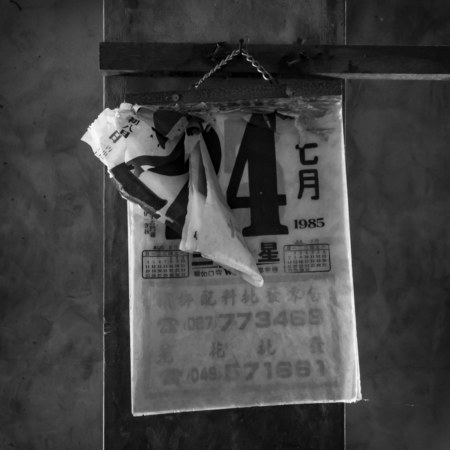

- This entry in the Taiwan Cultural Memory Bank suggests the theater closed in 1993, but the calendar on site suggests otherwise. ↩

- The final screening was reported by Liberty Times and China Times. ↩

Write a Comment