Near the end of my first summer in Taiwan I visited Bādǒuzi (八斗子), a rocky headland, coastal park, and major fishing port at the far eastern edge of Keelung. I went there on impulse, not knowing what to expect, just to see what was out there. Google Maps and Taiwan’s excellent public transit system make random explorations like this almost effortless: pick a point of interest and follow the directions—the digital equivalent of throwing a dart at a map. This post features a selection of retouched photos from this expedition alongside the sort of explanatory text I wouldn’t have been able to write back in 2013. Fair warning for arachnophobes: this post contains several gratuitous photos of giant spiders and other creepy crawlies!

First, about the name: Badouzi (Pat-táu-chí in Taiwanese Hokkien) has the same Indigenous roots as Beitou (Pak-tâu). Both are Hokkien variations of Pataw, a word in the language of the Basay People, usually considered to be the eastern branch of the Ketagalan People, the Indigenous people inhabiting the Taipei Basin and the northern shoreline of Taiwan when the Spanish arrived on the scene in the 1620s. From what I’ve read Pataw may have meant “shrouded in mist” (which certainly applies to Beitou) but nobody seems too sure of this translation and there’s no longer anyone you can ask. Although Ketagalan was once the lingua franca of northern Taiwan the language died out in the early 20th century, leaving a legacy of dozens or perhaps even hundreds of place names such as this one.

Badouzi was originally an island1 separated from Taiwan by a narrow channel. It was only in the late 1930s, during the construction of the enormous Japanese colonial era Northern Thermal Power Plant (北部火力發電所), that it merged with the Taiwanese mainland through land reclamation2. This power plant was decommissioned in 1981 and was abandoned for decades before construction of the National Museum of Marine Science and Technology (國立海洋科技博物館) began in 2012. I happened to arrive partway through construction but several of the museum’s more iconic buildings were already complete and can be seen here.

Fishing harbours can be found on both sides of the peninsula. Badouzi Fishing Port (八斗子漁港), to the west, is the largest in northern Taiwan despite only opening in 19793. To the east one will find the much smaller Zhǎngtán Village Fishing Harbour (長潭里漁港) about which little is written online. I started my walk around Badouzi at the smaller harbour after jumping off bus route 103, direct from downtown Keelung, and ended it at the much larger harbour at sundown.

It was a clear, warm, and beautiful day when I visited Badouzi for the first time. I wandered along the coastline, observing Taiwanese at play. A large group of people were out photographing shorebirds in Cháojìng Park (潮境公園) and many more were flying kites in the open expanse of the Environmental Rehabilitation Park (環保復育公園), a former landfill, thanks to strong winds coming off the East China Sea (東海). Along the way I couldn’t help but notice the unusual Chaojing Aquaculture Station (潮境海洋中心工作站), a museum outbuilding mostly suspended in air against the sloping hillside that marks the edge of Badouzi Coastal Park (八斗子海濱公園). I remember thinking, “Isn’t it peculiar putting an oceanic research facility in the sky?”

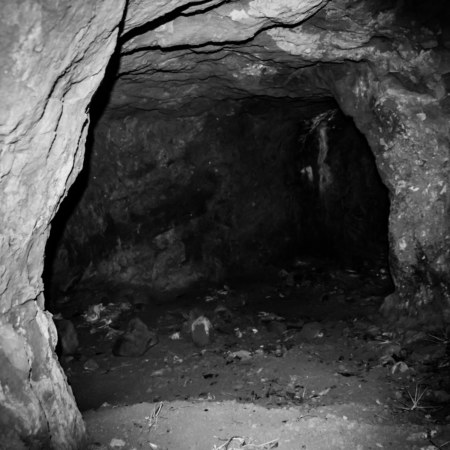

Nearing the northern shoreline I went looking for a way up and over Qīdòushān (七斗山), the mountainous outcrop that forms the bulk of the peninsula. Unfortunately the main trail was closed to the public for some reason—well, it was probably stated on the sign posted at the locked entrance but I couldn’t read it at the time. I didn’t really want to walk back the way I came so I decided to follow an overgrown footpath leading up and along the cliffside. Soon I left the sanitized parklands behind and entered the wilderness. The trail diffused into the undergrowth but I forged on, already committed. This brought me within sight of a mysterious cave that immediately aroused my curiosity. I went to investigate.

Stooping to enter the cave, I brought out a torch to light up the interior. The rough-hewn walls suggested it wasn’t natural—and an assortment of trash on the ground confirmed a human presence in the past—but what would this cave have been used for? I contemplated military applications4 as I crept deeper into the darkness. Soon my flashlight captured motion: a giant centipede, probably in the genus Scutigera, scuttling along the wall. Yech! Shining my light up ahead I saw several more multi-legged horrors writhing in the gloom. Repulsion overtook curiosity and I retreated to the outside world, almost stumbling headlong into a giant spider hanging at eye level near the cave entrance5.

Nephila pilipes is a species of golden orb-weavers known as the “human face” spider (Rénmiàn Zhīzhū 人面蜘蛛) in Chinese, named for the distinctive patterning that appears on the dorsal (top) surface. Females can grow very large, about the size of the palm of my hand, and spin large and unusually strong webs up to several meters across. Their silk is robust and I have, at times, actually bounced off the thick strands used to secure a web high in the air. They are indeed venomous, but not lethally so, and you’ll find them all over Taiwan.

After inspecting that first golden orb-weaver I surveyed the immediate area but found no sign of an onward trail. The cave had been cut into a sheer cliff and not far to the right there was another drop, presumably down to the sea, although it was obscured by shrubbery. I wasn’t about to backtrack and lose precious daylight so that left me with only one option: trudge through the jungle, hopefully to meet up with the path that hasn’t been accessible down by the park.

I set out into the jungle but only made it a few steps before coming face to face with another giant spider. I ducked under the bottom of this web, came up, and cursed—yet another spider blocked my path. I looked to my left and saw even more webbing. Crouching down, I surveyed the sky and saw the silhouettes of spiders absolutely everywhere—the entire forest, a webbed labyrinth! I advanced in the only direction open to me, stopped short of another web, and pondered my next move. And so it went, step by step, cautiously slinking through a silky maze. It was not unlike the sort of diabolical puzzles commonly found in the point-and-click adventure games of my youth—and for that reason I persisted in completing the quest without resorting to waving a stick around to clear the air.

Fifteen minutes later, having successfully slipped by dozens of arachnid sentinels, I hoisted myself onto the raised walkway running through the forbidden part of the coastal park. Here, with some amusement, I found an educational plaque introducing the very spiders I had eluded mere minutes before. I continued down the unmaintained stretch of path until reaching another barrier—the counterpart to the one back at the base of the hill. I jumped over it and sauntered over to the lookout at Highland 101高地, presumably the highest point on the peninsula. I didn’t realize it at the time but the purely functional name of the various “highlands” in the park are former military observation posts. Decades ago, during the long, dark years of the KMT authoritarian era, this entire area would have been off-limits to the public.

Highland 101高地 offers a fantastic vantage point to observe the surrounding coastline and it is worth taking a moment to identify several features in this photograph of the view to the east. The city high on the hillside is Jiufen, one of the biggest tourist attractions in northern Taiwan. The mountain immediately to the left is Jīlóng Mountain (雞籠山), literally “chicken cage mountain”, named for its resemblance to a traditional woven bamboo chicken cage6. In the foreground is the long and skinny Shēn’ào Headland (深澳岬角), another intriguing coastal landscape and fishing port worth exploring.

I came down out of the hills into a place by the name of Wàngyōu Valley (望幽谷), evidently another locale popular with Taiwanese for reasons that are somewhat obscure to me. I descended the stone-cut stairway, leapt over a dead cat, and soon arrived at the intertidal zone of the Dàpíng Coast (大坪海岸).

The rocky shoreline was mostly deserted so late into the afternoon. I wandered from place to place, inspecting coastal landforms sculpted by wind-blown grit and taking care while framing the landscape in my camera lens. These surreal images speak for themselves.

This coastline is teeming with Ligia exotica, a species of isopod commonly known in Chinese as Hǎizhāngláng (海蟑螂, literally “sea cockroach”) that I previously wrote about here. I also noted several outcrops of fossil shell beds along the shore, not an uncommon occurrence in this part of Taiwan. Most of the north coast is sedimentary rock uplifted and slightly tilted to one side.

With daylight fading I exited the coast and meandered along the docklands next to the harbour. Here I found an abandoned boat formerly with the Keelung City Rescue Brigade (基隆市救難大隊) and the Badouzi Fishing Harbour Oil Depot (八斗子漁港油庫), among other points of interest. Despite its status as the largest fishing port in northern Taiwan there wasn’t too much activity when I visited. Most of these boats probably sail long after dark, judging by the preponderance of incandescent bulbs.

At the very base of the harbour I found a grungy old building along Yúgǎng First Street (漁港一街). I had no idea what it was when I visited but now that I’ve taken a closer look at the photographs I suspect it might be an ice factory—with loading cranes for filling cargo holds with ice to maintain the freshness of the catch, some of which is destined for sale at Keelung’s all-night Kanzaiding Fish Market.

With night falling I returned to the highway to catch a bus back to Keelung and then home to Taipei. Writing about this random adventure nearly four years after it took place leaves me somewhat removed from the visceral experience of actually being there—but the photographs I captured act as keys to memories that have lain dormant all this time. I didn’t know very much about Taiwan at the time but I’ve learned a lot more about the area while researching this piece and wish to return some day. Hopefully these images have also aroused your interest in this scenic part of the beautiful northern shore of Taiwan.

- Curiously, this 1856 map of coal seams along the northern shore suggest that Badouzi was not an island. ↩

- The Japanese also constructed a railway to transport coal to the power plant in Badouzi. Originally known as the Jīnguāshí Line (金瓜石線, 1937–1962), it extended from what is now the Agenna Shipyard on the eastern side of Keelung Harbour (基隆港) to the coastal mining town of Shuinandong in Ruifang. Several years after this railway closed part of it was absorbed into the Shēn’ào Line (深澳線, 1967–2007), which grew to serve the nearby (and now-demolished) Shen’ao Power Plant, built in the late 1950s and snaked through the mountains to connect with Ruifang Station (瑞芳車站). More recently the Shen’ao Line was rehabilitated for tourism—much like the more famous Pingxi Line (平溪線)—and two stations have opened up near Badouzi: the eponymous Badouzi Station (八斗子站) on the coast just east of the peninsula and Hǎikēguǎn Station (海科館站) further inland and close to the museum. All of this information is contained here in a footnote as I saw no sign of the railway line on my first visit to Badouzi—and indeed, neither the railway line or the museum had officially opened when the photographs in this post were shot. Read more about the old railways of the area in this great article from Bios Monthly (Chinese, of course). ↩

- That the power plant officially closed two years later is probably no accident. I haven’t done the research but the port was probably planned as a means of sustaining the local economy after closing the power plant. ↩

- Decommissioned bunkers and observation posts are scattered around Badouzi and much of the park but I wonder if there’s any chance the cave predates the Japanese invasion of 1895? This stretch of coastline saw a lot of action in the latter decades of the 19th century. ↩

- I sometimes joke that the spiders aren’t so bad unless you get one in the face. And yes, that has actually happened more than once in the years of exploring Taiwan’s many remote and neglected places. Haven’t had a bite yet, praise Dogar and Kazon. ↩

- Keelung itself is probably named after the mountain but it no longer shares the same characters. Qing officials renamed it “base of prosperity” in 1875 to make it somewhat more respectable than “chicken cage city”. Nowadays the mountain itself is located beyond the borders of Keelung in Ruifang. ↩

Write a Comment