Guóbīn Commercial Building 國賓商業大樓 is an ugly ruin in the heart of Zhongli, a city of around half a million people in Taoyuan, Taiwan. Built at the dawn of the booming 1980s, it was home to a variety of entertainment businesses over the years, and appears to have been mostly abandoned sometime around the turn of the millennium. Much to my surprise I’ve not found much about this place online, which suggests whatever newsworthy calamities befell this derelict commercial building predate the era of digital journalism. Without any sources to draw upon I can only make some educated guesses about what I captured during a brief visit in the early days of 2017.

As with many ruined entertainment complexes in Taiwan this one isn’t completely abandoned—you’ll still find a run-of-the-mill betel nut stand out front, for example—but most of the rest of the building is a dangerous, crumbling ruin. The second floor is occupied by the remains of Shuǐzhōnghuā Jiǔdiàn 水中花酒店, a hostess bar and karaoke club named after a famous song by Cantopop legend Alan Tam 譚詠麟. A jiudian is a place where men drink and cavort with women but they’re not exactly brothels and sex isn’t necessarily on the menu (despite what the blatant appropriation of the Playboy bunny logo might suggest1). Such disreputable establishments are commonplace in Taiwan and dozens more can still be found in this part of Zhongli.

The fire that swept through the third floor cleansed it of anything that would reliably identify what it had been. The charred remains could be those of a bar, restaurant, nightclub, arcade, or something else entirely. Business records suggest this was a dessert shop for much of the 1990s but it’s hard to say if it was still in business when the blaze broke out.

The fourth floor is home to the smaller of two cinemas found within the building, part of the eponymous Guobin Theater 國賓大戲院. Business records suggest the theater occupied both 4F and 5F since 1980 but I have my doubts about this. The lower theater is unusually cramped—just look at those concrete beams running along the ceiling. It also looks like the screen would have been illuminated from behind, an unusual setup for old theaters in Taiwan. Finally, the crude printed sign welcoming customers on the fourth floor contrasts with the proper sign on the fifth. I would speculate that the theater on the fifth annexed the fourth floor at some point in the 1990s.

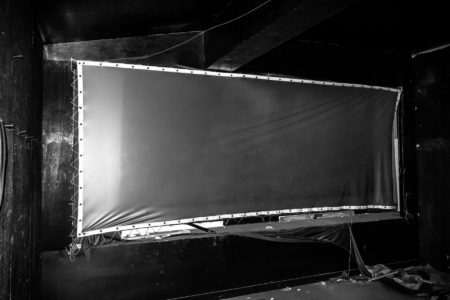

It is clear from the layout and design of the fifth floor that it was purpose-built to be a movie theater. Here you will find a projection room—but no projectors, for the building is far too exposed to have retained anything of value—as well as a big silver screen. The screen is framed by red velvet curtains advertising a defunct brand of soft drinks2. Globalization has taken quite a toll on Taiwan’s beverage market and many classic brands, Warinta 華年達 among them, went out of business long ago.

The sixth and final floor of the building was a regular venue for niúròuchǎng 牛肉場3 (literally “beef fair”), a common form of bawdy entertainment combining song and dance with striptease, essentially a kind of Taiwanese burlesque4. Originally known as the Guobin Cabaret 國賓大歌廳5, this particular establishment was part of a wider circuit of clubs operating in the shadows of the martial law era. It isn’t at all unusual for sleazy karaoke bars and other adult-oriented businesses to colonize old entertainment complexes in their twilight years—but in a remarkable twist this venue was in continuous operation throughout the building’s history!

The sixth floor is in bad shape after a fire, quite likely the same blaze that struck the third. It is difficult to discern whether the cabaret was already out of business but it is not uncommon for fires to break out in abandoned buildings in Taiwan. The interior of this building is in very rough shape and there are holes in the floor in several locations. Be sure to take appropriate precautions should you wish to explore this ruin—although I should note that as of 2019 the entire building has been sealed and there is no obvious means of entry.

One additional mystery presents itself after a close inspection of the exterior of the building. Here we can discern the remains of a sign for Lánjíyǎ 蘭吉雅, the Chinese transliteration of the Lancia brand of automobiles. Was the ground floor once a car dealership, was this merely an advertisement, or might it have been something else? Sometimes these posts have a way of jostling loose additional information so I’ll be sure to update this post if I learn anything new.

Update: as of 2020 this building has been demolished. Nothing remains.

- There is at least one article out there explaining what jiudian culture in Taiwan is all about—but you’re on your own here. I won’t vouch for the quality or accuracy of what you find. ↩

- Such advertisements were not uncommon in the 1970s and 1980s. If you’re curious to see another example have a look at this theater in Puli. ↩

- Apparently the euphemistic name is derived from the more direct descriptions of the show: yǒuròu 有肉 or ròuròu 肉肉, which simply refers to exposed flesh. Anyone literate in Chinese might get something more out of this than I did. ↩

- Niurouchang is part of a continuum of risqué practices including electric flower cars (電子花車), funeral strippers (葬禮脫衣舞), and cross-dressing shows (反串秀). ↩

- The business changed hands several times over two decades, undergoing a name change in the process. In the late 1980s it was known as Guóxīn Cabaret 國新大歌廳 (as seen in this vintage poster from 1989) and, still later, Dōngfāng Cabaret 東方大歌廳, but I suspect it reverted to its original name at least once. The English translations here are my own. ↩

已拆除。