On several recent trips to Ho Chi Minh City I spent some time wandering around Cholon, a vast and historic Chinatown located about five kilometers west of the downtown core of colonial Saigon. Originally settled in the late 17th century by ethnic Chinese settlers, the Hoa People 華人, it was known by its Cantonese name, Tai-Ngon 堤岸 (literally “Embankment”, but it is also roughly homophonous with “Saigon”). Later the Vietnamese dubbed it Cholon (“Big Market”) after the forerunner of the modern-day Binh Tay Market. The Hoa people were once the majority in Cholon but many fled persecution in the aftermath of Fall/Liberation of Saigon in 1975, and again during the Sino-Vietnamese War. Nowadays the Hoa people only account for approximately 5% of the population of Ho Chi Minh City (less than half the proportion of ethnic Chinese living in Toronto, my hometown) but their imprint on the streets of Cholon is readily apparent, particularly in the form of the many distinctive temples and guildhalls of the district.

Initially I was interested in visiting Cholon to explore someplace that I might be at least somewhat familiar with. I’ve learned a lot about Chinese folk religion in Taiwan so I was keen to see how these traditions manifested in Vietnam. My curiosity was piqued after reading that Cholon was settled by Chinese people around the same time as Taiwan, albeit with a different mix of migrant groups. Whereas Taiwan was settled primarily by Hoklo (Fujianese) people and a sizeable Hakka minority, Cholon attracted many more Cantonese and Teochew people1. As with many overseas Chinese the migrant groups of Cholon organized themselves according to geographic origin and shared language, establishing guildhalls (huìguǎn 會館) to serve the needs of their communities2. These guildhalls combined commercial, social, and spiritual functions, acting as business associations, philanthropic organizations, meeting spaces, and halls of worship. Nearly every temple featured in this post began as a guildhall built to serve migrants from specific parts of China. Before we begin I should mention that these temples blend Taoism, Buddhism, and Chinese folk religion without much concern for boundaries. Now for a whirlwind tour of some of the many temples of Cholon…

Thien Hau Temple

Founded in 1760 by Cantonese immigrants from Guangzhou, the Thien Hau Temple3 (Vietnamese: Chùa Bà Thiên Hậu; Chinese: 穗城會館天后廟4) is easily the most famous temple in Cholon, and you’ll regularly witness huge groups of tourists passing through. As with many of the other temples in the area this one venerates Mazu (also known as the Empress of Heaven; Mandarin Chinese: Tiān Hòu 天后), goddess of the sea and protector of seafarers and fisherfolk. Mazu worship is common among pre-modern diasporic Chinese communities—migrants prayed for safe passage through treacherous waters and built temples in her honour after establishing themselves abroad.

Tam Son Guildhall

Across the street from the Thien Hau Temple is the Tam Son Guildhall (Vietnamese: Hội Quán Tam Sơn; Chinese: 三山會館), built by settlers from Fuzhou in Fujian province, very close to the birthplace of Mazu. Most sources suggest this temple was founded in 1839 but there appears to be some uncertainty about this date. Mazu is worshipped here, as you might expect, but the main shrine venerates Mẹ Sanh (Chinese: Zhùshēng Niángniáng 註生娘娘), a fertility goddess. I was most intrigued by an unfamiliar representation of Tǔ Dì Gōng 土地公, the god of land, and a shrine to his constant companion, the tiger deity Hǔ Yé 虎爺. The small shrine on the opposite side of the temple features Chì Tù Mǎ 赤兔馬, the warhorse belonging to famous general Guān Yǔ 關羽 (also known as Guān Gōng 關公, who appears elsewhere in the same temple), and two idols representing Wú Cháng Guǐ 無常鬼 (literally “Ghost of Impermanence”), an underworld deity charged with administering divine justice5. This being’s distinctive headpiece is emblazoned with the phrase Yī Jiàn Fā Cái 一見發財 (“Get Rich at First Sight” and “Become Rich Upon Encountering Me” are two translations I’ve seen around the web) and supplicants pray to this god for luck and prosperity.

Quan Am Pagoda

Quan Am Pagoda (Vietnamese: Chùa Quan Âm; Chinese: 堤岸觀音廟) is another famous temple in Cholon regularly frequented by tour groups. Officially known as 溫陵會館 (Vietnamese: Hội Quán Ôn Lăng), this guildhall traces its history back to 17406 and derives its name from a traditional term for Quanzhou, a historic port in Fujian. This particular temple has much more of a Buddhist focus than the others, and the primary object of worship in this temple is Guān Yīn, a Bodhisattva commonly known as the Goddess of Mercy in English7. An altar featuring three figures Sān Bǎo Fó 三寶佛) surrounded by the Eighteen Arhats 十八羅漢 also caught my eye as I wandered through. This holy trinity almost certainly includes Amitābha 阿弥陀佛 but the others are unknown to me. Finally, I was intrigued to find another small shrine to Hu Ye, the tiger god, and something I hadn’t seen before: a mythical chimera known as Pí Xiū 貔貅 (中文), which comes in male and female forms distinguished by the number of horns (one for male and two for female).

Phuoc An Guildhall

Phuoc An Guildhall (Vietnamese: Hội Quán Phước An; Chinese: 福安會館) is less of a mystery than the others; this hall was constructed in 1902 to serve the immigrant community from Fu’an in northeast Fujian. The primary deity worshipped here is the red-faced general Guan Yu (hence the Chinese name, Guān Dì Temple 關帝廟, “Emperor Guan”), but you’ll also find many others deities including Sūn Wù Kōng 孫悟空 (represented here as Tề Thiên Đại Thánh 齊天大聖), the Monkey King from the 16th century Chinese classic Journey to the West. I was most impressed with the beautiful ceramic murals inside this particular temple; this art form, jiǎn nián 剪黏 (“cut and paste”), is more often seen on temple exteriors. Even the traditional tripodal censer is covered with fragments of porcelain! The stone guardian lions out front also seemed quite unconventional.

Nghia An Guildhall

Nghia An Guildhall (Vietnamese: Hội Quán Nghĩa An or Chùa Ông; Chinese: 義安會館) dates back to 1819 and was built by people from Chaozhou (also known as Teochew). As with several of the other guildhalls profiled here this one derives its name from a very old term for Chaozhou, one that dates back to the 5th century in this case. This particular temple is known for its gorgeous woodcarvings. As with the previous temple this one is dedicated to Guan Yu, not only a god of war but also trade and commerce.

Ha Chuong Guildhall

Founded in 1809, Ha Chuong Guildhall (Vietnamese: Hội Quán Hà Chương; Chinese: 霞漳會館) is closest in appearance to the southern Fujian style of temples seen across much of Taiwan. The formal name of this guildhall derives from an ancient term for Zhangzhou in southern Fujian. This is also primarily a Mazu temple but there’s quite an assortment of other shrines to be seen—as well as a deity I’ve not noticed before, a dark-faced judge with a crescent moon on his forehead, Bāo Zhěng 包拯 (appearing here as Lord Bao 包公). Chéng Huáng 城隍, the City God, also makes an appearance, as does Tài Suì 太歲, a personification of Chinese astrology.

Quynh Phu Guildhall

Quynh Phu Guildhall (Vietnamese: Hội Quán Quỳnh Phủ or Chùa Bà Hải Nam; Chinese: 瓊府會館 or 海南天后廟) was founded sometime around 1824 to serve the needs of immigrants from Hainan, an island in the far south of China not far from Vietnam. The formal name of this guildhall is derived from the archaic name for Hainan. As with several of the others this temple also reveres Mazu, but it doesn’t look much like the others. The colour scheme is much brighter and more vibrant, the woodcarvings more personable.

Le Chau Guildhall

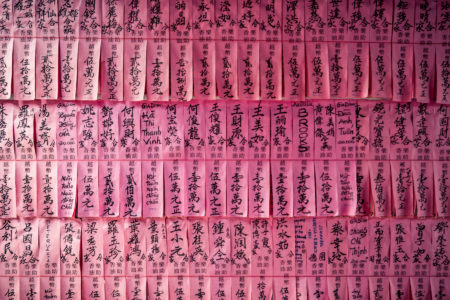

Le Chau Guildhall (Vietnamese: Hội Quán Lệ Châu; Chinese: 麗朱會館) was founded in 1896 to honour the master goldsmiths, silversmiths, and jewellers who introduced the lucrative trade to southern Vietnam. Since this guildhall was built by and for tradespeople rather than an immigrant community the name alludes to the trade itself, meaning something along the lines of “beautiful jewel”. On the inside, the altars are also different from the others, in that they feature only tablets with characters drawn in gold calligraphy.

Ong Bon Pagoda

Finally we arrive at what is popularly known as the Ong Bon Pagoda (Chùa Ông Bổn), an outlier from the others for several reasons. This is the oldest temple on the list, dating back to 1730, and also the only one built to serve two migrant communities—from Quanzhou and Zhangzhou. This explains the formal name of the underlying guildhall, 二府會館 (Vietnamese: Miếu Nhị Phủ8), which translates to “Two Prefecture Guildhall”. Enshrined here is Tu Di Gong, the god of land, known to Vietnamese as Ong Bon. English language sources refer to Ong Bon as the god of “wealth and happiness” but in Taiwan we usually think of the god of land as a protective deity, warding off evil and ensuring the health and welfare of the local populace with the assistance of Hu Ye, his divine tiger steed.

Hopefully this has been an informative introduction to Chinese temple culture in Cholon, Ho Chi Minh City’s historic Chinatown. This post is by no means comprehensive, but it comes close to covering all the traditional Chinese temples and guildhalls around Cholon9. That being said, I’m still learning about Chinese folk religion so I may have made some mistakes in the text—please feel free to let me know in the comments or by sending an email.

- Cholon was originally settled by ethnic Chinese fleeing the collapse of the Ming dynasty prior to Vietnamese conquest of the Mekong Delta. These people became known as the Minh Hương (initially 明香 and later 明鄉). ↩

- Guildhalls and similar organizations are common throughout the Chinese diaspora. In North America they were often called benevolent associations. In much of the rest of Southeast Asia it seems like the term kongsi 公司 (literally “company”) was more common. I’m not very familiar with these organizations as they don’t often come up in my research into Taiwanese history, possibly because Han Taiwanese became the majority not long after settling the country. Previously I wrote about a Chinese association founded in Taitung during the Japanese colonial era but that’s an unusual case. Japanese colonization subsumed many regional identities into a generalized Hoklo majority, particularly in the case of Taiwanese Teochew, who I wrote about here. ↩

- Every temple has an official name in Chinese—but what we think of as “Chinese” is really hundreds of languages, most of which have no standard romanization system. All of these temples also have Vietnamese names, but some of them translate the name of the guildhall whereas others represent the main deity worshipped in the temple. English names in common usage usually derive from Vietnamese so any mistakes or inaccuracies are multiplied. I’ve been a bit loose in using the names of individual guildhalls but the alternative is calling almost everything a “Hoi Quan Pagoda”, which is less than ideal. ↩

- Officially this is a guildhall named 穗城會館; the first character is a traditional shorthand for Guangzhou followed by the character for “city”. ↩

- In Taiwan this deity is almost always two gods, Qī Yé 七爺 (Seventh Lord) and Bā Yé 八爺 (Eighth Lord), one tall and white and the other short and black. ↩

- Most English language sources say the temple was founded in the “19th century”. Here I am going with the date mentioned in the Vietnamese Wikipedia entry. In Chinese folk religious tradition the temple is the organization, not the structure, so we’re mostly concerned with when the guildhall itself was founded, not when the physical form of the temple was constructed. It is very likely that every temple featured in this post was renovated sometime in the last several decades—and those renovations can ↩

- If you’re paying close attention you’ll probably realize that Quan Am is Vietnamese for Guan Yin. Here she is depicted in Chinese folk style with a special flask (jìngpíng 淨瓶, “pure bottle” perhaps) in her left hand, purportedly containing the elixir of life or holy water. ↩

- A direct translation of the Chinese name would be Hội Quán Nhị Phủ; the “Mieu” in the name means “temple”, not guildhall, and results from a somewhat garbled translation of 二府廟. ↩

- Two more leads on temples not covered in this post: Nghia Nhuan Guildhall (Vietnamese: Hội Quán Nghĩa Nhuận; Chinese: 義潤會館) founded in 1872; and Minh Huong Temple (Vietnamese: Đình Minh Hương Gia Thạnh; Chinese: 明鄉嘉盛會館), founded by Ming dynasty loyalists in 1797, and only open to the public before noon. ↩

Thanks for your sharing! Thien Hau Temple is best place to visit when you come to ho chi minh city!

Hello, do you know where the cemeteries were? my grandfather was buried in Cholon in 1941 but I am wondering if the cemetery still exists with the urbanization. Thanks a lot

Hello Lili, it sounds as if most older cemeteries have been or are in the process of being removed from the central urban area. Find A Grave provides some hints about where you might continue your search.

Chinese Community in China Town or Cho Lon contribute a big role in Saigon economic development and their culture such as temple, pagoda, markets, foods are something we need to preserve. Thanks

Great guide with historical knowledge. Thanks for sharing.

Why do some pagodas (Tam Son) have a figure at the eaves on the right holding the character ri (sun) and on the left yue (moon)?